In Graphite, users build their artwork by connecting nodes together in a graph. When they want to organize and reuse a complex group of nodes, those may be encapsulated together as a subgraph in which one parent node represents the functionality of its children. In fact, many of the nodes provided in Graphite are themselves subgraphs built out of other nodes.

Double-clicking on nodes backed by a subgraph will display the subgraph's interior. Double-clicking nodes that are, instead, backed directly by Rust source code will open a code editor.

Any (sub)graph can import/export data from/to the outside world. For example, a reusable subgraph may receive an imported image then use several nodes to process it and finally export the result. Or the root-level artwork graph may import the animation timestamp and render a frame of the artwork then export it to the canvas.

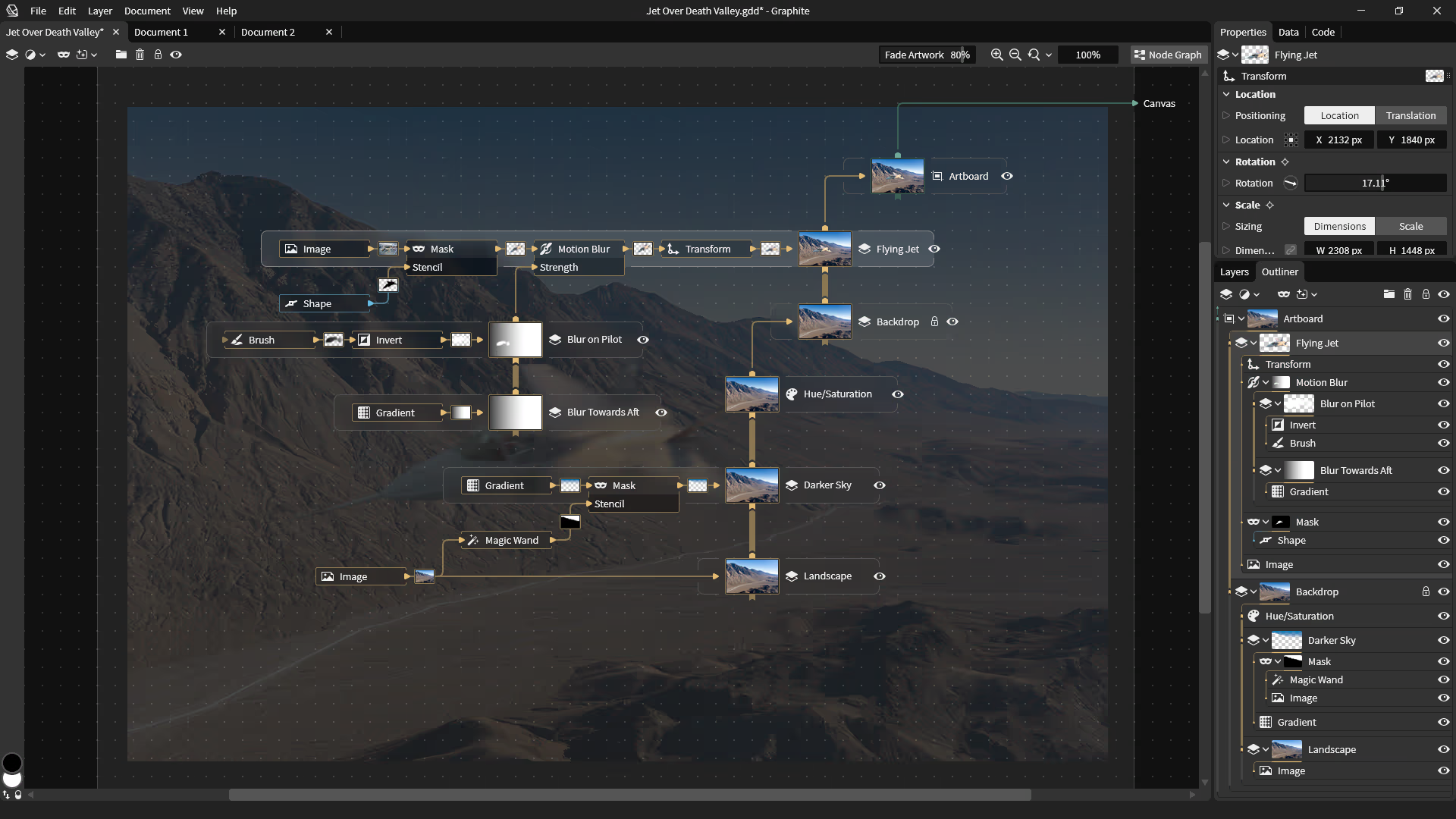

In the Graphite editor UI, here is an example graph of artwork that imports no data but exports its content to the canvas:

The graph shown above represents the full artwork, meaning it's the root-level graph in its document. But there is nothing special about that graph compared to any subgraph. To avoid the confusion of calling it a graph or subgraph which comes with implications about user-facing concepts in the context of a document, we will use the less-ambiguous term network in the context of Graphene's internal concepts and code base.

Networks

A node network can be thought of as a box containing a finite set of nodes that are connected together as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). The network is only concerned with its own node-to-node data flow. But to interact with the outside world, data can be imported into the network and exported out of it. From the inside, those imported/exported data sources/destinations are connected to the other nodes in the network. From the outside, a network can be considered a "black box" that is simply fed inputs and can be executed to produce outputs.

More coming soon...